Introduction

For 5,000 years – besides occasional conquest and periods of indentured servitude – the resources of the Shetland Islands have belonged to the industrious and resilient people who have lived here. This is an idea that sits at the heart of modern community wealth building: that communities should reap the benefits of their own resources.

Shetland’s resources – our land, seas, and air – have long captured the attention of outside interests. As the economic value of these resources have risen and fallen, extractive businesses have come and gone. The most dramatic manifestation of this was the crushing poverty faced by Shetlanders under the unscrupulous lairds of the 19th century. The second most dramatic example of our resources capturing significant outside attention is happening today and relates to developments that (unlike oil and gas, where the product merely passed through the isles), will produce exportable commodities like hydrogen, using Shetland’s land, sea, and air (or more specifically, our wind).

On Shetland’s history of dealmaking

It is fifty years since the late Jo Grimond described the threat of a “free-for-all” of industrial developments as he stood in the House of Commons defending the interests of the Shetland community, as encapsulated in the Zetland County Council Bill. A year later the Bill would achieve Royal Assent and become law – providing unique powers to this day – as the Zetland County Council Act (1974).

The ZCC Act came about because local councillors recognised that the laws of the time wouldn’t be sufficient to prevent Shetland being taken advantage of by big business. Rather than simply settle for that reality, and in the face of seemingly limitless corporate resources, they set out to deftly change the law.

The ZCC Act gave the local authority unique powers to:

Undertake the compulsory purchase of development sites (the transfer of the sites for Sullom Voe Terminal, Sella Ness & Scatsta, with the aim of controlling development and benefiting the whole community, rather than a handful of individuals or land speculators).

Participate in financial markets, to borrow and take part in projects and commercial endeavours.

Establish the council as the harbour authority for most of Shetland’s waters outside of Lerwick & Broonies Taing, initially at 3 miles, now out to the 12-mile territorial limits.

Set up the harbour account, which could be used “for any other purpose which in the opinion of the Council is solely in the interests of the county or its inhabitants” (one such modern use of these funds being the establishment of the ORION project, which we’ll come back to later).

It wasn’t the legislation itself that earned the oil return for the community, rather it acted as the foundation for subsequent deals struck by oil executives and council officials.

The ZCC Act underpinned the 1978 Port & Harbour Agreement, which was the deal made between the terminal operator and SIC, for the local authority to provide commercial port services and jetties for the tankers. This commercial return would go into the harbour reserve account, and occasionally be used to top up the charitable trust.

The other important deal was the disturbance agreement of 1974, the detail of which was kept secret until 1989. This provided the seed for the Shetland Charitable Trust, which was paid around £81 million in total by the oil companies up to the expiry of the agreement in 2000. That initial capital has now grown significantly through investment, and the annual returns are what fund things like Clickimin Leisure Centre and the Mareel arts centre.

On the situation today

A conservative estimate of Shetland’s current development trajectory is that we are 5 to 10% of the way into the wind, hydrogen, and energy infrastructure development boom, meaning 90 to 95% of the industry has yet to be built either in or around Shetland.

Alongside wind, hydrogen produced by electrolysis is the critical commodity in which Shetland has an inherent production advantage over many locations in Europe. Whilst the hydrogen has a market on its own, hydrogen is also needed to produce synthesised hydrocarbons, methanol, ammonia, and a range of other exportable commodities.

A major reason why Shetland’s resources are so attractive is to do with the quality of our wind, both onshore and offshore. Around 70% of the cost of making hydrogen comes from the cost of the electricity used. In Shetland, the quality of wind means that each unit of electricity can be generated more cheaply than almost anywhere else.

‘Capacity factor’ is the commonly used measure for how efficiently a wind farm generates electricity, based on how consistent the wind blows in a particular area. For example, a 100MW wind farm with a 25% capacity factor would produce 25MW over the period considered.

The Scottish mainland’s average capacity factor for onshore wind is 31%. Shetland’s average capacity factor is a world-beating 51%. This is a measure of the quality of our wind, it’s strength and consistency. Think of it like this: if one of the Viking turbines was erected in the average Scottish location, and the other in the average Shetland location, and each were paid 6p a unit to generate, the single turbine in Shetland would generate an additional £450,000 per year compared to the mainland UK one.

We shall return to community benefit in more detail but will note for reference that £21,500 would be the amount that would be paid as community benefit anywhere in Scotland from that machine, including in Shetland. That number represents 1.87% of the annual output value of the Shetland machine (3.07% for the Scottish machine’s output), despite Shetland offering an additional 65% generating value advantage over the average Scottish location.

The quality of Shetland’s wind acts as a potent incentive for hydrogen developers to build (or acquire) their own onshore or offshore windfarms, more so than in any other UK location. The reasons for this are severalfold:

Firstly, if the hydrogen developer doesn’t own the means of generation, they will have to pay for each unit used, leaking margin to the generator. In Shetland (again compared to the average Scottish location), a windfarm owner can generate 65% more power without any increase in the capital cost of putting up the turbines, meaning each unit of electricity is cheaper, increasing the profit on the hydrogen, and avoiding any costly transmission charges from the grid.

Secondly, the development of a new export industry can only come from very large-scale production. Scatsta and Sullom Voe are not just significant assets for the Shetland community but are of national significance when it comes to hosting large scale hydrogen production facilities. The two sites have the size required to support the equivalent of 40 Viking windfarms-worth of electricity input for subsequent conversion into hydrogen. At this upper limit of scale, at just 5% profit margin (note that many developers are currently achieving UK Gov subsidy support at margin levels greater than 10%) the annual profit from these facilities would approach £500 million per year, with 18GW of wind, producing a little over 2 million tonnes of hydrogen for export each year. On the current trajectory, all this value would leave Shetland.

Thirdly, if large enough electricity demand centres can be established in Shetland in the form of hydrogen production facilities, it could lead to a monopoly scenario, where the facility operators act as the only routes to market for the power, eliminating normal competitive barriers for further wind developments, and consolidating influence over Shetland’s long-term prosperity into the hands of a few remote shareholders.

An important distinction is that whilst oil was produced from reservoirs outside of our territorial limits and piped into Sullom Voe for handling, hydrogen is different, in that its raw ingredients require Shetland’s land, sea and air. These are resources that exist ‘on’ Shetland, the place where the desired molecules will be electrolysed into existence, and we have some of the best natural resources in the world to do this. Any threats (veiled or otherwise) to bypass Shetland doesn’t work for hydrogen as they did for oil and gas. This community has inherent geographic advantages that are not going anywhere, and which should bolster our collective ambition.

On the need for action now

The foresight and ambition evident when the oil deals were made seems to have withered. There is therefore a need for urgent political intervention (both at local and national level) to prevent the kind of loss of control and overdevelopment that Grimond described 50 years ago.

To reiterate, this is a political issue for Shetland. The big businesses involved in trying to corner this opportunity are behaving as could be celestially predicted, and they are not breaking any rules in doing so.

The unyielding focus of long-term business strategy is to return economic value for shareholders first and foremost. Businesses can do good, and they often do, but only so long as it doesn’t compromise their ability to return economic value to shareholders. They can be led by moral, idealistic people, but the rules of the game require businesses to minimise and externalise costs wherever possible. One of the purposes of democracy is to constrain and manage these characteristics.

In this case, a fair share of value for the community from the use of Shetland’s land, sea, and air, represents a cost that big business will inevitably seek to avoid and minimise as much as possible.

On community benefits and ownership

In Shetland we have the dubious distinction of being unique amongst our Nordic neighbours in allowing - and actively promoting - the extraction of profits from our natural resources by external companies. The comparisons with Orkney and the Western Isles are no more flattering: both have secured better deals from their onshore wind projects than Shetland did with Viking.

The OIC will make more from their onshore wind project than Shetland does from Viking, despite the Orkney project being a third of the size.

In the Western Isles, the community has negotiated the equivalent of 100MW of onshore wind into community ownership, from a total development size of 500MW, which could return £15 to £20 million more per year than Shetland’s annual take from Viking (including the payments the Charitable Trust will receive for early participation), despite the windfarm only being 13% larger.

Community benefit payments (typically an annual fee of £5000 per installed MW) exist as a tacit acknowledgement that communities don’t benefit adequately from large developments, and so they represent a kind of disturbance payment.

The Scottish Government may soon drop the idea of community benefit in its current form, as they progress legislation on “Community Wealth Building”, which prioritises shared ownership and participation, over the enablement of extractive business models.

There is good reason for this evolution of thinking. A 2021 study by Orkney-based Aquatera looked at 13 Scottish windfarms (4 privately owned, 9 community owned), and found that the average direct financial return from a private windfarm was £5,000 per installed MW per year for the community (the same as Viking), compared to an average direct return of £170,000 per installed MW per year from the community-owned windfarms (34 times higher).

The same principles can be applied to the production of Hydrogen and derivatives; anything less than shared-ownership or material project participation will short-change the Shetland community.

There are many ways in which community ownership can be achieved which don’t require risky investment of public funds. Examples include the use of a community owned site in exchange for an ownership share in the development, or, as the Western Isles are doing, a negotiated ownership share option that can be exercised after successful project construction and government-backed contract is in place for generation (if power) or production (if hydrogen). This example is an extremely low risk way of making a significant return, as the contracted price for generation could be known in advance of the investment to be worth more than the cost of the borrowing to acquire the stake.

The SIC’s ‘energy development principles’, which were ratified in Dec 2022, show little ambition for additional value realisation beyond the current Scottish minimum community benefit model: “Shetland Islands Council believes that £5,000 per installed Megawatt (indexed) or c2.5% of generation value is also an appropriate quantum for Community benefit payment to the Shetland community for all offshore wind”, and “Proposed offshore development anywhere in the seas surrounding Shetland must include a Community Benefits package of the same relative value as now established for onshore projects”.

The option that represents best value for the community should be clear; that ownership is preferable to being a recipient of benefits.

On the ORION Project

The stated aims of the ORION project are to:

“Enable offshore oil & gas sector transition to net zero by electrification, utilizing initially onshore and then offshore wind”

“Transform Shetland’s current dependency on fossil fuels to affordable renewable energy to address fuel poverty and improve community wealth”

“Create on Shetland a green hydrogen export business at industrial scale by harnessing offshore wind power and creating new jobs”

In January 2020, The Director of Infrastructure Services presented a project initiation document to elected members covering the “Shetland Energy Hub” concept. In the meeting, the council authorised the Director of Infrastructure services to undertake various tasks, including to “deploy project staffing and resources […], for an initial period of three years financed from the Harbour Account”, and to “promote Shetland’s energy assets and attributes to local and external energy production and distribution sectors”. Since this was being financed from the harbour account, it was the implicit view of the council that this project would be “solely in the interests of the county or its inhabitants”, as per the ZCC Act.

By mid-2021, the Shetland Energy Hub project was gathering pace. The project had been renamed ORION, an oil industry advisor had been appointed, a partnership with the Oil & Gas Technology Centre established, and an industry steering group set up that consisted of BP, EnQuest, Equinor, Shell, SSE, TotalEnergies and Siccar Point Energy, who would meet bi-monthly. The project governance document states that the steering group are “industry stakeholders [who will] benefit from a successful outcome” and who will “provide project guidance, support, engagement and steerage”.

In addition to the industry steering group, bi-weekly meetings were being held between EnQuest and SIC officials and consultants to jointly work towards electrification and transformation opportunities in the Sullom Voe Region.

In that time, direct participation or shared community ownership does not appear to have been discussed, although not all minutes are in the public domain to confirm this. Neither is there any public record of the decision to appoint EnQuest as the chosen custodian of this new industry, despite EnQuest stating publicly that they had “secured an exclusivity agreement in 2022 with the Shetland Islands Council to progress new energy opportunities at SVT”, something that would sit outside of the scope of the current site agreement. We can but hope that this agreement includes terms that are in the interests of this county and its inhabitants, given the unassailable position this provides EnQuest, and any of their wholly-owned subsidiaries.

In November 2021, a group of 29 signatories lodged a petition to challenge the delegation of authority from the elected members to the council officials. Their short and incisive petition read: “The request for approval of the above [delegation of authority] requires a massive transfer of powers and responsibilities to non-elected officials, who will be making decisions which will have far reaching implications for our islands and seas.”

The petition was unsuccessful, and the council approved the “delegated authority to the Chief Executive, or her nominee, to pursue Council and Shetland interests through engagement with other key partners in future developments and the securing of community benefits from these. This will include engagement with UK and Scottish Governments and their agencies, potential developers, the Shetland Community and local partners, neighbouring islands with similar issues and opportunities and across relevant economic sectors.”

Whilst the ORION project has undoubtedly been professionally managed and successful in promoting Shetland’s advantaged natural resources and geography to industry, it is not clear that this has maximised the wider community’s positioning for long-term benefit or opportunity to participate in the use of our own resources. If jobs, disruption payments, or other ‘benefits’ were the desired outcome in simple exchange for world-class resource extraction, it’s little wonder that big business is queuing up to build in Shetland.

On how we can move forward constructively

Besides our natural resources, Shetland is also endowed with abundant expertise in every one of the areas that would be required to deliver a cutting-edge energy development. Indeed, as a collective people, we arguably have more innate capability in the areas of financing, contracting, project delivery, commissioning, and safe asset operations than many of the corporations currently vying for position to utilise our resources.

Those who suggest that ambitious outcomes can only be delivered by large corporations have either only ever worked for a large corporation, or not been involved in progressing the kind of project being discussed here. Similar viewpoints abounded 50 years ago, including Tam Dalyell’s probing question of Grimond: “Does the Zetland County Council have the expertise to become a harbour authority? Most of us who know something about harbour authorities appreciate what an enormous amount of expertise is involved”. We decided we did, then we proved it.

As the number of deals that are made with developers grow, so does the urgency of action. Although Shetland has some of the best onshore and near-shore wind development sites in the country, they are finite, and more control is needed over the speed and scale of development.

For Shetland then, there are two priorities:

Secure a significant and fair proportion of the economic value of Shetland’s resources through community wealth building / ownership, rather than benefit schemes.

Secure increased control of developments, to prevent overdevelopment.

The prioritisation of ownership should be built into revised energy development principles and, with determined political leadership, special statutory powers should be vigorously explored that require developers to partner with community entities (rather than having a voluntary ‘community benefit’ system).

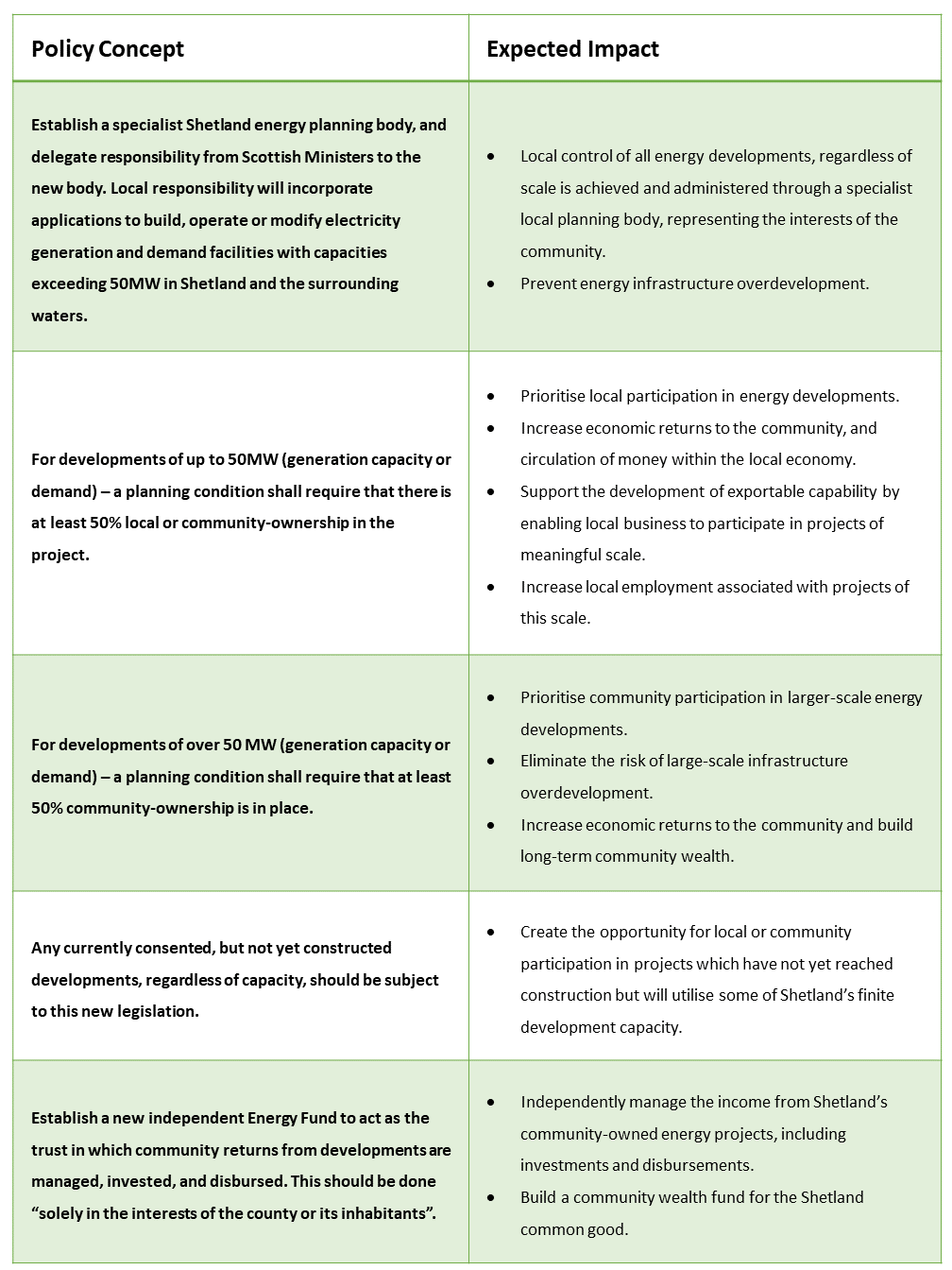

The following policy intervention concepts should be urgently explored with the aim of providing the necessary framework for local control of developments in Shetland in the coming years:

Shetland now has two possible futures. In the first, extractive business models financialise our world-class resources on an unprecedented scale, whilst traditional industries are displaced, and our schools, services, transport, and social care sectors increasingly struggle to make financial ends meet.

Alternatively, we could have a future as a more prosperous, egalitarian community. We could harness the output of our own resources to generate power and produce commodities at a proportionate scale, with the statutory protections in place to eliminate the threat of a development “free-for-all”. That could be us: but time is short.